Secret masterpieces

DISCOMFIT, v. This week I considered writing “discomfit” in my novel draft and then thought, “Wait, are ‘discomfort’ and ‘discomfit’ related? Is it epenthesis?” Epenthesis is a fancy linguistics term for when speakers insert an R into the middle of a word, like how in some regional varieties of US English, speakers say “warsh” instead of “wash.” It turns out to be irrelevant to the question I was asking, but don’t you like knowing that we have a word for that phenomenon?

Anyway, “comfort” comes to us through French from Latin, and it’s pretty straightforward: “com-” is a prefix that sometimes means “with, together,” and is sometimes an intensifier (more!) and “fort” is from the word for strength. So a thing that comforts you is a thing that makes you stronger. Isn’t it good—comforting, even—to think of life’s small pleasures as a source of strength?

“Discomfort” is equally straightforward, being the absence of comfort. It’s a thing that saps your strength. It weakens you.

“Discomfit” is a little bit of a surprise, because it’s not “discomfort” without that extra R. I should have suspected that “-fit” at the end of “discomfit” is descended from Latin’s verb for “to do, to make,” FACERE. The other pieces of “discomfit” are our old friends, the intensifying prefix “com-,” and the negative prefix “dis-.” These pieces don’t add up to much: not, more, do?

Latin had the verb CONFICERE and then CONFIRE, and respectively, these meant “prepare” and then “prepare, accomplish” (don’t be fooled by the N in CON, that prefix is exactly the same one we’ve been looking at this whole time). So these two verbs are about preparing and accomplishing—doing more!—and in Old French, their opposite arrives: desconfire, to defeat—to undo all your hard work and preparations. That’s where we get “discomfit.”

The contemporary definitions of “discomfit” are as follows: (1) to defeat; (2) to frustrate or thwart the plans of; (3) to embarrass or perplex or disconcert. Definitions 1 & 2 are less common and they come from the original Latin. Definition 3 is the more common contemporary one and, as you might suspect, it comes from all of us mixing up “discomfit” and “discomfort.” Don’t feel bad. Apparently we’ve been doing this since the 1520s. It’s not a mistake anymore, it’s standard usage. Language is the ultimate in collective action: if enough of us do it together, we can transform anything. Although I think we can all agree that it is embarrassing, perplexing, and generally uncomfortable to have our plans thwarted, as this word thwarted my plan.

I think many of us are discomfited, as in perplexed, as in frustrated, and sometimes as in defeated, by the state of the world right now, so I’ve seen a lot of discussions of comfort. We are all asking ourselves and each other: in the face of overwhelming fear and uncertainty, what gives you strength?

I did not read any Capital-R Romance this week, but I did watch French historical lesbian yearning masterpiece Portrait de la jeune fille en feu (Portrait of a Lady on Fire), which is as beautiful as everyone has told you, and also as heartbreaking.

Other than the tragic ending, my only complaint about the film is that there should have been more hats.

Women did work as portrait painters in 18th-century France, and the two most famous of these were Adélaïde Labille-Guiard and Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, both of whom worked at Versailles in the latter half of the century. As you can see from these examples of their work, hats are crucial.

Portrait of a woman, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, 1787

Self-portrait with two pupils, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, 1785

Self-portrait in a straw hat, Élisabeth Vigée le Brun, after 1782

Marie-Antoinette and her children, Élisabeth Vigée le Brun, 1787

The film’s hatlessness—or really, its wiglessness—is a stylistic choice probably meant to make us feel closer to its characters, who look more modern with their hair unwigged and uncurled. More like us.

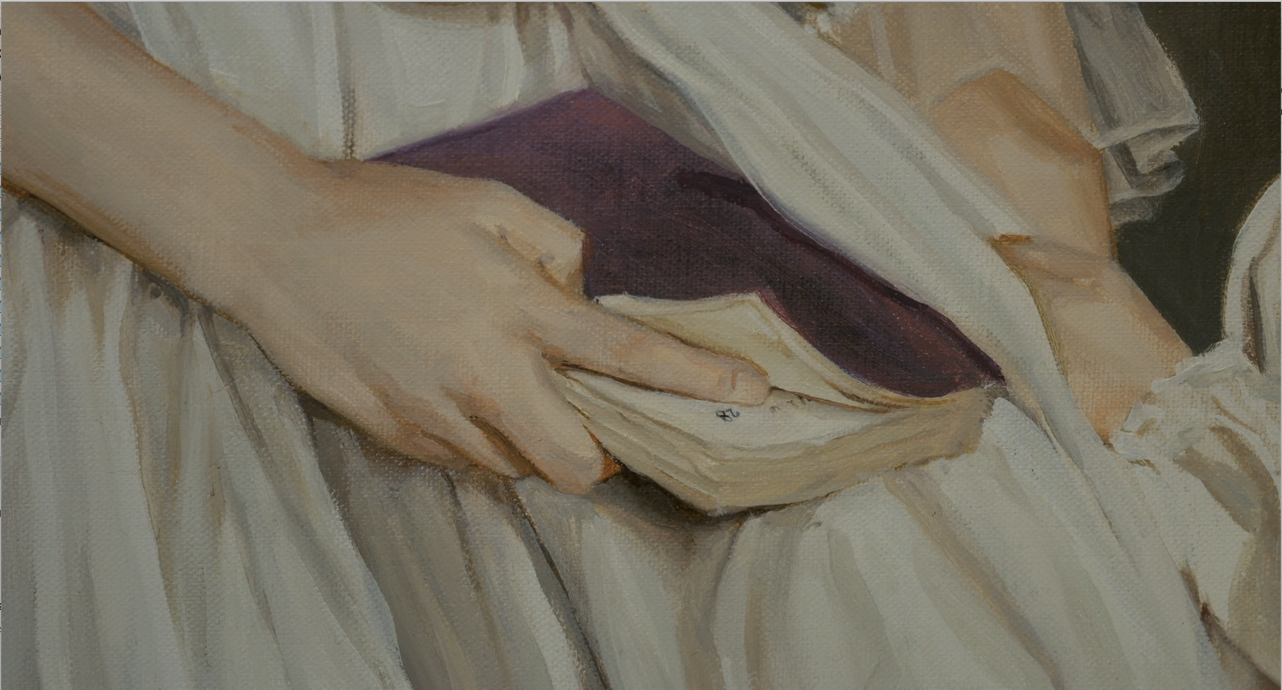

Certainly the film wants us to feel close to these characters, since the story moves from one enclosure—a magical man-free island somewhere off the coast of Brittany or Normandy—to increasingly smaller and more intimate enclosures: the old stone house where Héloïse lives, Marianne’s studio/bedroom, Marianne’s bed, the life-size framed portrait of Héloïse, the miniature oval portrait of Héloïse, and most intimate of all, the nude self-portrait that Marianne draws between the pages of Héloïse’s book. These small spaces, locked away, preserve their love. But both women are away of what they have been locked out of: Marianne chafes at being forbidden to paint male nudes, which would allow her access to the more respected genres of painting history and myth; Héloïse has never been allowed to run free, not until she meets Marianne, and even so she can only run as far as the edge of the island, whose boundaries both protect her from and deny her the rest of the world.

So much of the film turns on Marianne and Héloïse’s ability to see each other, to allow themselves to be seen. When Marianne arrives at the house, she is told that Héloïse exhausted the previous portraitist by refusing to pose for him. Marianne discovers her predecessor’s work, a portrait of a woman in a green dress whose face is a blank stretch of canvas. It’s a horror, and Marianne burns it. But she’s forbidden to tell Héloïse the truth, and Héloïse would refuse to sit for her if she did, so Marianne unintentionally recreates this faceless portrait, first by secretly sketching Héloïse in pieces, and second by assembling those pieces into a portrait that Héloïse hates, and third by scraping the face off the hated painting.

It is impossible for me to see any of that without thinking of Balzac’s 1831 short story “Le Chef-d’œuvre inconnu” (The Unknown Masterpiece). Briefly, here is what happens in this short story: a young artist named Nicolas Poussin (a real historical artist, one of the greats, whose life Balzac took a lot of liberties with) goes to visit an older artist named Porbus (same), and encounters the elusive genius Frenhofer (at last, a fully fictional character). Frenhofer has been working for years on a masterpiece that nobody has ever seen. It is a figure painting of a nude woman, entitled La Belle Noiseuse (The Beautiful Troublemaker). Frenhofer claims he cannot finish the painting because he can’t find the model he needs. He’s traveled all over the world looking for the right woman, but he can only find women who have some of the right body parts (yes this is extremely sexist and gross), not one woman who is wholly perfect. Porbus and Poussin are dying to see this masterpiece, but Frenhofer won’t let them. He doesn’t want anybody to see it until it’s finished.

“Wait,” says Poussin, “I just happen to be dating The Hottest Babe in the World. Can I trade her to you in exchange for a look at your painting?”

Frenhofer agrees to the deal. Poussin’s girlfriend Catherine, The Hottest Babe in the World, is not happy about being voluntold to get naked in front of a weird old guy, but she sacrifices herself to give Poussin a shot at seeing the masterpiece so he can grow up to be the greatest French painter who ever lived. La Belle Noiseuse gets finished at last, and Porbus and Poussin get to go up to the attic to see it.

It’s a fucked-up mess. (Remember: nobody knows about abstraction yet.) A huge, dense chaos of brushstrokes that looks like nothing, except down in the corner of the canvas, one foot—the most beautiful, lifelike foot ever painted—emerges from the cloud.

Poussin and Porbus are puzzled and horrified and generally rude as fuck about this painting, and Frenhofer doesn’t understand why they don’t see what he sees. After they leave, he burns the painting and his whole studio with himself inside it.

This story is iconic. It was Picasso’s favorite short story, presumably because he saw it as prophetically foretelling his own work, to the point that Picasso deliberately bought and lived in the building in Rue des Grands Augustins where Frenhofer supposedly lived. The story has also been made into several film adaptations, one of which is called La Belle Noiseuse. It plucks the story out of Balzac’s idea of the 17th century and plops it down in the 1990s. It’s four hours long and most of that time is spent with the camera focused on the stunningly beautiful naked body of a young woman, so it’s pretty faithful to the original Balzac, really.

While watching Portrait, I initially thought of La Belle Noiseuse because of a very simple similarity: it’s the only other film I’ve seen that lavishes such long shots on a hand creating an image. Both films luxuriate in the sound of the charcoal meeting the paper or the brush meeting the canvas. (Also, obviously, both movies are French and about painting.)

But Portrait and “The Unknown Masterpiece” overlap in other ways, such that Portrait feels like a response: Marianne drawing Héloïse in pieces is Frenhofer trying to assemble a Frankenbabe from disparate women, and Portrait makes clear that chopping Héloïse up like this, without her consent, is wrong. And it produces a bad painting to boot. Marianne burning the paintings that fail to capture Héloïse also calls Frenhofer to mind.

Technical expertise, in Portrait, is insufficient to make great portraiture: you have to know your subject. Marianne can’t paint Héloïse right until Héloïse consents to pose, to be seen. This thought never occurs to any character in “The Unknown Masterpiece,” in which Catherine, The Hottest Babe in the World, is only of use as a sacrifice on the altar of male genius. Her inner life is not considered; her exterior is all that matters. She is literally objectified.

Portrait not only prizes Héloïse’s consent, it prizes her gaze. While Marianne paints her, Héloïse is able to look back at Marianne. Their knowledge of each other is mutual. Marianne makes a painting of Héloïse for herself and then gives Héloïse a self-portrait to keep. These gifts, not made for future husbands or to be sold for money, are an exchange totally unlike the one in “The Unknown Masterpiece,” where a real woman is traded in for a painted one. Poussin sells his girlfriend for art. Marianne and Héloïse keep each other in the only way they can—enclosed, secret, seen by each other, unknown to the world.

A still from the movie

Plus, if you’re into that sort of thing, there are a ton of Easter eggs for art history nerds. The cliffs on the island look like every Monet painting of Étretat (incidentally also the location of a Maupassant short story about a painter and a female model), and there are many “lone figure overwhelmed by a sublime landscape” shots, you know, that Caspar David Friedrich shit. There’s a shot that recalls Jean-François Millet’s 1857 painting The Gleaners. Many candlelit shots recall Rembrandt. And, naturally, you can’t make a French lesbian art history movie without a wink at Courbet’s Le Sommeil.

Anyway, Portrait was breathtakingly sexy, romantic as hell, and I cried at the end. Content warnings: it will break your fucking heart, a supporting character commits suicide (off-screen, before the story), pregnancy/abortion.

This week in small-r romance was mostly about comfort rereads.

Tough Guy (cis m/sorta androgynous femme cis? m, both gay, contemporary) by Rachel Reid. This absorbed my attention for almost three hours, which is a minor miracle. Rachel Reid is, as always, very, very good at what she does. Perfectly paced, very sweet, and also a thoughtful exploration of anxiety and masculinity. Content warnings: homophobia, anxiety, violence, a main character’s parents are not very supportive of his queerness, a supporting character commits suicide.

Heated Rivalry (gay m/bi m, both cis, contemporary) by Rachel Reid. A reread, previously discussed here. It’s unusual for me to reread something three months after finishing it, but this book is so engrossing. It was what I needed this week. Honestly I could go for another round. I love these two talented, determined, clueless people very much. This is how I described the story on twitter, should you require an advertisement:

Felicia "Ray" Davin @FeliciaDavin

I [25M] have been secretly hatefucking my professional rival [25M] for 8 years every chance we get. Last time we had sex, he used my first name during, and afterward we cuddled and he made me a tuna melt. What does it mean?

April 3rd 2020 13 Retweets 78 Likes

Content warnings: homophobia (including slurs, violence, the fear of getting outed), an abusive father, a mother who committed suicide.

Think of England (m/m, both cis and gay, historical) by KJ Charles. Also a reread, because one I opened that door, it was impossible to close it. It’s very hard to pick a favorite KJ Charles novel because they are all perfect, but this one is close to my heart because it’s the first one I ever read. A classic pairing of a big dumb Golden Retriever type and a slinky intellectual type, plus a country house mystery, plus the most incredible tension and pacing. I was going to say “country house murder mystery” in the previous sentence, but I realized on reread that in fact, the first murder that happens in this book is committed by one of the protagonists. And I support him. I also love that you can see KJ Charles’s love of Victorian pulp come through—the references to Curtis’s uncle the explorer, the bottomless pit in the caves. Content warnings: a lot of murder, violence, suicide, voyeurism/blackmail, moments of dubious consent, homophobia, antisemitism, racism.

Proper English (f/f, both cis and lesbian, historical) by KJ Charles. After I reread Think of England, I couldn’t resist its prequel, previously discussed here. (There’s a strong chance I’m gonna reread all of KJ Charles.) Just like in Think of England, the murder that happens in this book—another isolated country-house affair—is a real highlight. I love both Pat and Fen so much, and they’re such wonderful opposites. It’s also delightful to me that it’s not practical, self-assured Pat who makes the first move, but more-than-meets-the-eye Fen. Proper English is also a great companion piece to Portrait of a Lady on Fire because so much of it is about being seen and known and understood for who you are. Content warnings: murder, racism, misogyny, homophobia.

In things that are neither Romance nor romance, I finished Priestdaddy by Patricia Lockwood. It’s a memoir about her bonkers but endearing family. Apparently if you’re a Christian minister/preacher/reverend of some Protestant denomination who has a family, but you feel called to become a Catholic priest, there is a loophole that allows you to become a Catholic priest and keep your family. So Patricia Lockwood’s dad is a Catholic priest.

This book is so gorgeous and genuinely laugh-out-loud funny that it has rendered me speechless. The whole time I was reading it, I kept pausing to explain why I was laughing to J, who has also read it, and all I could do would be to whisper “The Rag” or “Bananas for the Lord” and wipe the tears out of my eyes. J understood, happily.

Priestdaddy is warmhearted and beautiful and very, very funny—comforting, certainly—but it doesn’t shy away from serious, upsetting things. Content warnings: discussion of the author’s suicide attempt, mentions of other suicides, discussion of child rape by Catholic priests, mentions of the author’s rape (in the form of alluding to the poem she wrote about it), death from cancer, pregnancy/abortion.

I hope you are all taking comfort wherever you can find it. See you next week!