Furbelows and dandies

FURBELOW, n. I’ve been reading Valerie Steele’s Paris Fashion: A Cultural History and J. A. Barbey d’Aurevilly’s Du Dandysme et de G. Brummell (usually called The Anatomy of Dandyism in English) as research for the romance novel I’m writing that is set in nineteenth-century Paris, because there’s only so many times I can get away with “and then they took their clothes off.” Sometimes I have to say what people are wearing, or which clothes, exactly, they’re removing, and then I have to know the right vocabulary for that. Even though I read historical romances like it’s my job (it is my job), trying to write one confronts me with all the things I don’t know. Hence, research.

Of these two texts, Paris Fashion and Du Dandysme, it’s the one in English that has the most words that are new to me. Isn’t it amazing that you can speak a language natively for thirty-plus years and still come across a word and think “uhhh what”?

Anyway, “furbelow,” as it turns out, is a flounce of fabric or some kind of fancy pleated or puckered addition to a gown or petticoat and according to the OED, “often in plural as a contemptuous term for showy ornaments or trimming, esp. in a lady’s dress.”

“Furbelow” is an etymological mystery. It comes from “falbala,” a word with the same meaning of a trimming, which is in many Romance languages. The OED said “falbala” was origin unknown, but I checked the Trésor de la langue française and that entry says it might come from Franco-Provençal “farbella,” which means “rag” or sometimes indicates something without value. So a little scrap that you add to your clothes.

I came across “furbelows” in the following passage of Paris Fashion, in which Steele is explaining the power of various guilds in eighteenth-century France:

The trimming of a dress was more important than its cut, since the shape of dresses changed only slowly and even an “ordinary” robe à la française was highly decorated. As a result, the couturières [seamstresses or dressmakers] were less influential than the marchandes de modes [fashion merchants or milliners]. Even wealthy and fashionable ladies might keep their dresses for a number of years, but they re-trimmed them frequently, and that was where the milliner came in with her stock of ribbons, ruffles, furbelows, and lace. (Italics in text, translations provided by Steele earlier in the book)

Steele provides a 1756 François Boucher painting of Madame de Pompadour, mistress of King Louis XV, with many, many furbelows pictured:

We love a François Boucher painting here at Word Suitcase. Spend 8000 hours painting every tiny detail of the furbelows on the dress, yesss. Sourced from Wikipedia.

I’m guessing Mme de Pompadour could get a whole new dress whenever she wanted and didn’t have to bother with changing the trimmings.

Steele’s book is very entertaining and I’m still not finished with it. I stopped in the middle to pick up Du Dandysme, which had been gathering digital dust on my Kindle for an embarrassing length of time, after Steele wrote this passage about its author, Jules-Amédée Barbey d’Aurevilly:

Because d’Aurevilly wore exaggerated 1840s-style fashions [in the 1880s] and was surrounded by young men, rumors circulated that he wore corsets and was secretly gay, to which he allegedly replied, “My tastes lead me there, my principles permit it, but the ugliness of my contemporaries disgusts me.”

This is the best possible response to rumors about your gender and sexuality: “That sounds like a you problem.” What a fucking door-slam of an answer.

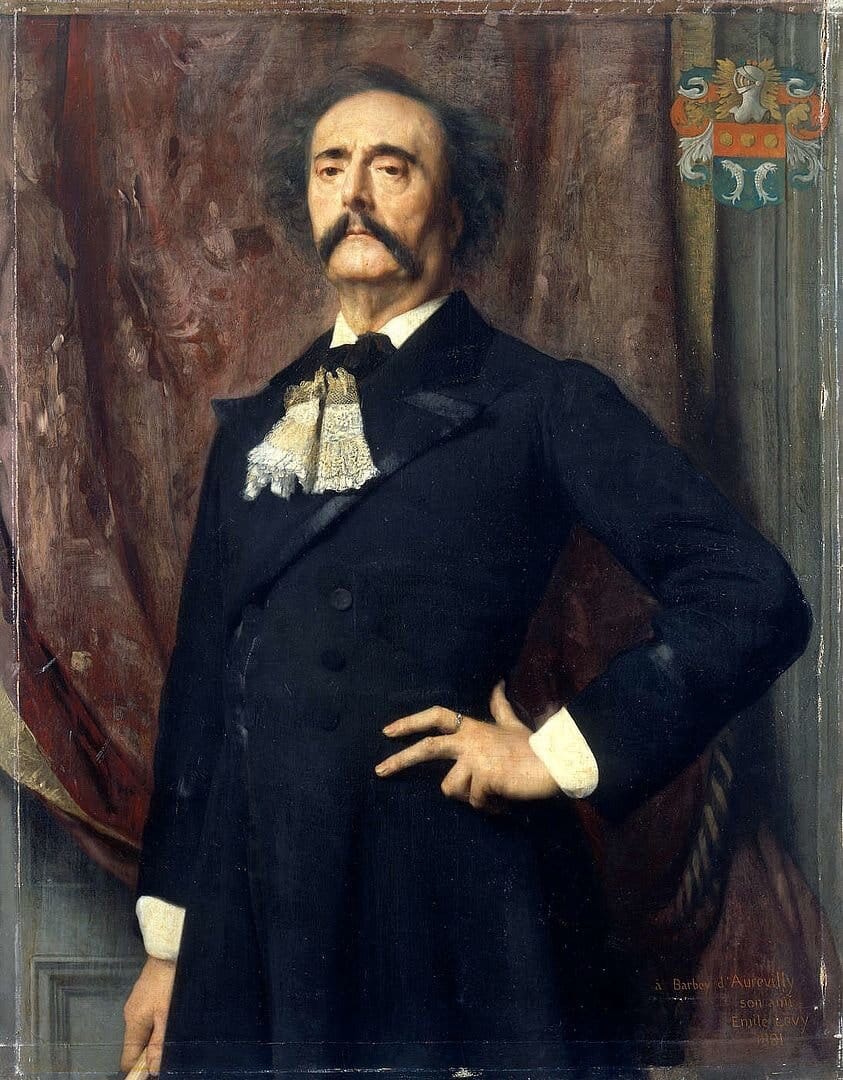

Here, by the way, is seventy-four-year-old Jules-Amédée in the 1880s still rocking a lace jabot (that’s the white lace at his collar) and still on his way to steal your man:

Painted by Émile Lévy in 1882. Source from Wikipedia.

I almost wrote a chapter of my doctoral dissertation about d’Aurevilly’s 1874 collection of short stories Les Diaboliques (sometimes translated The She-Devils) because Jules-Amédée and I share a love of scheming bitches. I dropped the chapter for the very scholarly reason that it seemed like my committee would let me scrape by without it, and I was desperate to be done. Nothing personal, Jules-Amédée.

Anyway, in another world, maybe I would have read Du Dandysme (1845) years ago. In this world, I didn’t die of crying-related dehydration in grad school and this funny little essay became my Capital-R Romance read this week.

It’s not useful as a source if you’re, say, writing a scene where you need to know what your characters are wearing under their frockcoats (d’Aurevilly said none of your fucking business), but it is a guide for how to be a stylish queer who gets invited to all the best parties, which is even better. D’Aurevilly, not a dandy himself but “an unclassifiable romantic eccentric” according to Steele, is writing against everyone who said that a dandy is just a man in a stylish suit. That suit, by the way, would be free of furbelows and any such frivolous ornaments; dandies were known for their stark simplicity. The phenomenon originated in Regency England (1811-20) and was epitomized by style icon George “Beau” Brummell, whose biography d’Aurevilly is very loosely writing.

Mostly, d’Aurevilly is here to talk about a particular fashion subculture and its attitudes. He says we should not define dandies by their clothes, but by their way of wearing them, their elegant indifference. Dandyism requires a kind of too-cool-for-school detachment. At one point, d’Aurevilly laments that Brummell and other dandies are obsessed by “dignity,” which is, he says, a sad result of all the English being unavoidably contaminated by Puritanism. Is there a more French complaint?

Anyway, if you’re looking to become a dandy, here are some tips:

- Act superior.

- Present yourself as the perfect combination of artifice and nature.

- Don’t follow the rules; play with them.

- Don’t toss your witticisms; let them drop.

(D’Aurevilly clearly knew how to do that.)

Dandies are “stoics of the boudoir” and “Seeming is being for Dandies just as it for women.” In the French, that’s “Paraître, c’est être pour les Dandys comme pour les femmes” (83, in a footnote). And, most precious to me personally, in the last sentence of this meditation on dandyism, d’Aurevilly writes:

Natures doubles et multiples, d’un sexe intellectuel indécis, où la grâce est plus grâce encore dans la force et où la force se retrouve encore dans la grâce, androgynes de l’histoire, non plus de la fable, et dont Alcibiade fut le plus beau type chez la plus belle des nations ! (117-8)

These double and multiple natures, of an undecided intellectual sex, where grace is more grace in strength and strength finds itself once more in grace, androgynes of history and not of myth, of whom Alcibiades was the most beautiful example in the most beautiful of nations! (Translation is mine.)

“Intellectual sex.” You know what that sounds like to me? Gender. The thing about living in a very categorical society that divides men and women is that it’s going to make everyone hyperaware of anybody who is even just stepping one toe outside their category, let alone the people who overturn the system just by existing. So it’s not surprising to me that d’Aurevilly had thought deeply about gender, but it’s always cool to find references in older texts where living outside of society’s strict gender norms is treated as admirable and praiseworthy.

Then we get to the Alcibiades part. Much like when I encountered the word “furbelow,” I went “uhhh what.” In this context, what matters is not so much who Alcibiades was in Greek history (a statesman, a military leader, a student of Socrates, also a famous beauty), but what Alcibiades meant to d’Aurevilly and his nineteenth-century French audience. Here are some paintings that will help with that.

First, Alcibiades Being Taught by Socrates (1776) by François-André Vincent, which is just a normal representation of how people look and stand when they are learning philosophy and definitely not posing and reflecting on how hot they are.

And here’s Socrates Tears Alcibiades from the Embrace of Sensual Pleasure (1791) by Jean-Baptiste Regnault, which—personally I would stop inviting Alcibiades to my orgies if his cranky teacher was gonna interrupt like this.

This scene is, apparently, kind of a theme because Jean-Léon Gérôme takes it up again in 1861 in Socrates Seeking Alcibiades in the House of Aspasia. (Aspasia was also a philosopher. She might have been a sex worker. Gérôme clearly ran with that.)

So what we have learned from these paintings is that Socrates was very invasive and Alcibiades was never on time to philosophy class. He was too busy being a babe who liked to fuck. I don’t know that the paintings are saying anything about Alcibiades being of an undecided intellectual sex—I would need a real art historian to comment on that, I’m over here driving art history without a license—but certainly the Vincent painting shows both grace and strength. And this is a comment on sexuality rather than gender, but I think the third painting is showing Alcibiades in bed with a woman (in his lap) and maybe also a man (in the shadows behind)? There is an even more mysterious figure behind his shoulder. I’m choosing to believe it’s queer.

Is any of this going into my novel? Probably not! But now I know what “furbelow” and “Alcibiades” mean, and so do you.

Speaking of the embrace of sensual pleasure, this week in small-r romance, I read

Indigo (m/f, both cis and het, historical) by Beverly Jenkins. This 1996 Black historical romance between Hester, a dark-skinned Black woman whose hands and feet are stained purple from her years in slavery making indigo dye, and Galen, a light-skinned Black man descended from a community of free people of color in New Orleans, is a classic of the genre that deserves its legendary status. It’s set on the cusp of the Civil War. Hester and Galen meet because she runs an Underground Railroad safehouse in Michigan and he gets into some trouble while on a mission to help some people get to the Canadian border where they can be free. Hester nurses Galen back to health. They feel drawn to each other, but she’s adamant that the gulf between their social statuses can’t be bridged by marriage, and that wealthy playboy Galen will lose interest and move on. He, meanwhile, is utterly lightning-struck in love with her and spends the whole book trying to prove it. Hester is someone who has always taken care of other people and done without for herself, so it’s very touching to see Galen lavish her with gifts and care and affection. There are also great moments of banter:

“Are you mocking my height, sir?”

“One cannot mock what isn’t there, petite.”

I kept thinking, while reading Indigo, of what rich visuals it has and what a great TV series it would make—appropriate for today’s newsletter, the story involves many beautiful gowns. Galen repeatedly asks Hester to remove her gloves when they’re alone together, because he loves her indigo hands just as he loves the rest of her, and the tenderness there is just breathtaking; with the right actors and cinematography, that scene on film would launch 10,000 gifs. There’s a glittering ball in New Orleans, a small-town prison break, and tense action scenes in the woods of Michigan. The book has a whole community of characters in it, many of whom go on to have their own romances in other books. Part of a happily ever after is building a life with friends and neighbors you trust, and this book gets that exactly right. And, as always, Jenkins weaves in so much history—details about Black soldiers in the War of 1812, and the Free Produce movement (i.e. goods grown or made by free people), and John Brown. She deftly makes the point that happiness can still happen against a painful historical backdrop: In the last chapter, Hester thinks, “What else could a woman like herself want from life? The end of slavery would make the picture complete, but until it occurred she would be thankful for life’s smaller joys.” A fantastic read. Content warnings: slavery, racism, violence, kidnapping, threat of rape, sex, pregnancy.

Sword Dance (bi cis m/nonbinary character attracted to men, fantasy) by A.J. Demas. If I had realized that this book, set in a fantasy version of the ancient Mediterranean, was about a country house party where someone gets murdered and the two protagonists have to solve the case while working out whether they can trust each other, and circumstances absolutely require that they kiss to avert suspicion, and also one of them is nonbinary, I would have read it so much sooner! As it is, I’m glad to have have read it now, especially since a sequel just came out. This is such wonderful trope-y fun and the pace is gripping. I loved it. Also, appropriate for this newsletter, there are some great descriptions of fashion, and those paintings of Socrates dragging Alcibiades away from the orgies have kind of the same vibe as this book’s murderous philosophy student club. Content warnings: slavery (I’m always on edge when secondary-world fantasy has slavery as part of its setting, but here it is treated as a moral evil), a main character is a eunuch (not by choice but he is at peace with it), murder, violence, rape (in the past), threat of rape, homophobia, transphobia, ableism (in the form of insults to a disabled main character), torture (in the past), sex.

Also this week, Word Suitcase was in very flattering company on this Book Riot list of recommended newsletters about books. If that’s how you found me, hello! Every Sunday is different—I never know what I’m going to write about until it happens—but I think this one more or less conveys the mood.